BUCKNELL

Let me start by saying I was mighty surprised when your kindly professor invited me here to the university to speak to all of you. I don’t get much chance, or much reason, to come up these parts too often.

‘Course, I only live a stretch up the road, just on the other side of Centralia. You know, the Ashland area. I’ve been living there much of my life. You can probably tell by the looks of me that it’s been quite a while. Most of it’s been pretty ordinary; worked in the mines for some thirty years, then settled down to run a small dairy farm ever since. That’s why I was so surprised when your professor called on me.

I said, “What the heck you want with an old mountain goat like me?”

I said, “What the heck you want with an old mountain goat like me?”

And he says, “Well, sir, YOU are an expert.”

An expert? Boy, I’d never been called that before. Been called a lot of things, but never that. So I asked him, “How the hell can I be somethin’ and not even know it?” That’s when he explained to me about the class and how you explore Pennsylvania history.

Just the thought of exploring anything appealed to me. When you spend twenty years with your thumb and fore finger wrapped around a set of udders, you’d be surprised what strikes you as real excitement.

So he says, “I’d like to have you come on up to Bucknell and share some of your perspectives on the Pennsylvania mining culture with my class.” I told him I didn’t know if I had any perspectives for him, but I sure had some stories to share.

“Stories will be fine,” he told me, “Stories will be just the thing.”

So, I’m here. But now I’m starting to realize I don’t have a whole lot to tell. Wasn’t much to it in those days. We lived in a camp and fought the terrain. Mining was rugged and dangerous, and you lived most of your life in the dark. It was especially tough for me, being the youngest in the camp at the time.

‘Course, I don’t need to stand here and tell a classroom full of history students about the sordid past of old Centralia; about the fire that devastated the town way back in 1908 and left the houses buckled and down-trodden; or about the current fire which burns under that cursed town as we speak. Probably enough coal still burning under Centralia to keep the flames ragin’ another two hundred years.

It’s a real shame what’s happened to that place; once so beautiful and alive, now alone, abandoned, desolate. The memory of old Centralia is now just a few puffs of noxious gas on the horizon.

(“Centralia Fire” PBS 1982)

Course, it could just be the penance for a place whose first establishment was a saloon full of the worst sorts of people; the kind of people who’d resort to murder, or worse. If you ask me, that town was hexed since the first settler touched a boot down on its craggy earth. Kind of depresses me to talk about it. Not the most uplifting tale in the world. But I don’t need to tell you guys about a bunch of folklore from these parts. I’m sure your minds are full of this sort of thing just from living on campus.

Christ, the only real beacon of light we had back then took place only in the summer. Bout two forms of entertainment out in this quarry region back then: cards and baseball. And I didn’t much like cards because I never had enough for the ante.

But when summertime rolled around and baseball season revved up, I was in my glory. Those were some times. All the coal companies in the area had their own teams composed of employees and other assorted ringers they could convince to join the cause.

Before long, there were enough teams to assemble into what we called the Company League. Some of the best ballplayers I ever saw played in that league and many of them for my very own company, Northern Coal. Boy, watching those games and being part of the excitement of that league actually made up for all the days I spent underground.

The canary in the coal mine.

Our team at Northern Coal was named the Canaries, after the birds we’d keep caged in the shafts. If we found a canary belly up, us miners knew the chamber was filled with gas and we better head for the surface.

The members of the baseball club, like the birds, dedicated a fair share of their time to the mine shaft, but all of the spare moments were spent down at old Panhandle Park. It was just a deserted cornfield with a split rail fence and some burlap sandbags thrown down in the shape of a diamond, but it was all those boys needed. And I swear they had a starting nine that would have rivaled any team in history.

That lineup is burned into my brain.

Leading off was a kid named Ralph McCoombs, a centerfielder. He was as fleet-footed as a deer and he earned the nickname “Orange-Dust” because he left a trail of it behind him when he motored around the base paths. That boy covered more range in the outfield on foot than an eagle could have by air, and he did so with little regard for his body. He’d crash through fences, other players, whatever came between him and the baseball. His teammates would joke that an “I-got-it” from Dusty took precedent over one from God himself.

He was a small man, short and slim with a mop of reddish hair and a matching, stubbly beard. His face was heavily freckled and if his skin were any fairer the man would have been transparent. He didn’t speak too much, only when spoken to, and people kind of viewed him as some kind of a mute. But I knew better. He was no mute; just not sure of himself, was all. On the field he was a hero. But he had nothing to offer aside from baseball, or at least that’s the way he saw it.

Panhandle Park looked something like this.

Barney “Chief” Caskill batted in the two-hole for the Canaries. And, let me tell you, this guy was by no means a chief. He didn’t have a single drop of native blood in his body, and he couldn’t have led a honeybee to a ripe blossom, let alone lead a team. Truth be told, the guy was the biggest follower you ever met in your life, which was just the reason why the guys started in on him with the “Chief” nickname. You could have talked Chief into doing just about anything if you sold it to him proper.

Some of the boys would joke that he was a chubby ballerina…heavy on gravity but light on his feet. And you’d have thought his imposing size would have dictated that Barney was some kind of power hitter. Really, he was more of a finesse player. He’d slap singles to the opposite field, drop down bunts, steal bases once in awhile, and play the best defensive first base you ever saw. He had the wingspan of an octopus and the soft hands of a surgeon. Nothing got past the guy, and his teammates knew their own abilities were amplified when Chief stepped in at first.

He was an endearing guy, though. He really was. Had a big, round moon of a face with squishy cheeks and a boyish grin. He always had his hair neatly buzzed, or shaved completely, and his chubby head and neck seemed to melt into his narrow shoulders in one glob before bulging back out above the belt.

Batting in the coveted third position was the right fielder, Rockford Slate. Some of the town folk had taken to calling Rockford by the name of “Clean.” Clean Slate they’d call him–mostly because they thought it was clever, like the saying. But some of his teammates found the nickname to be even more dead-on than most people knew, and they did a little adjusting. Started calling that man “Clean-Livin’.”

They did it on account of the fact that old Rockford Slate was the biggest goody two-shoes you ever laid eyes on. He could stand in at the plate and hit a baseball clear out of the county, or he could hunch in real close and take a screamer off the elbow without so much as a grimace. But you give that boy a shot of whiskey and he’d keel over before you could say “Cheers!”

Miners in the Anthracite region would routinely spend up to 10 hours per day underground.

Old Rockford was more the religious type than anything else. He didn’t get in no trouble, never gambled or drank, and you better believe he’d be the first boy in that chapel come Sunday morning. People like him sometimes make me nervous, and Clean-Livin’ did have that effect on me a little. I guess it’s because you know everybody needs to cut loose once in awhile, and a person like that is liable to explode should the occasion ever make itself necessary.

The nervous feeling disappeared pretty quick once I thought about the man’s purity as a hitter. He could hurt you in a million ways. He could hit one out, or he could clip a single. He could leg out an infield hit, or he could work his tail off for a walk; and no one dared run on his cannon from right. I can’t even count how many men were left frozen on third base, legs clanging together at the knees, at the prospect of tagging up on a lazy fly ball hit to Clean-Livin’. Folks knew better than to do something so foolish.

Quite a handsome man, I’m not afraid to say. Tall and muscular, very clean-cut. The guys used to joke, “Always clean-shaven…that’s Clean-Livin’.” Rockford would get a kick out of it, too.

The cleanup hitter was third baseman, Harrison Jones, and it didn’t take a scientist to discover the origins of his nickname: Grizzly Bear. Old Harry was a massive specimen. Pretty hairy, too. His shoulders stretched on forever, and his forearms were like twin ham hocks. He had the face of a caveman, with a scruffy, brown beard and a thin tangle of hair up top.

That gentleman sure could mash a baseball. I mean, he could really hit one into the stratosphere. I heard he powderized a ball once; hit it and it turned into dust right there before everyone’s eyes. I guess stories like these gave old Grizzly Bear quite a reputation for being the biggest and the strongest.

And let me tell you, he was primed to defend the reputation to any nay-sayer that came calling. By golly, if he didn’t prove his point almost every time.

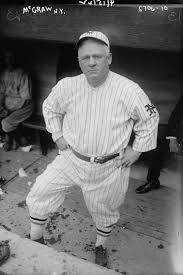

Protecting Mr. Jones in the five-hole was the catcher and player manager, Mr. John “McGraw” Williamson. On the field, he was the most cantankerous son of a bitch you ever met. Off the field, he was the most cantankerous son of a bitch you ever met. But on the bench, boy, this guy was a real gem. A real baseball mind he had. The boys all loved him. They’d have laid up in the train tracks for the man.

Still, most everybody else in town recognized him as a cantankerous son of a bitch.

New York Giants Skipper, John McGraw

You’d never mistake him on the field–always the one jawing with umpires, opposing players, obnoxious fans. Once, he even got in an argument with an old lady he was helping across the street. The sassy, old gal gave him one good swat across the head that day, I gotta tell ya. But that man loved to argue. Would eventually be his downfall, of course, but he sure didn’t mind that while he was nose to nose with someone, and if he did, he sure didn’t let it stop him.

That’s exactly how John Williamson got the nickname “McGraw,” after the old New York Giants skipper, maybe baseball’s most famous arguer. He may have still been playing in those days. But, I’ll tell you, I find it hard to believe even the genuine article could have out-argued Mr. John Williamson.

He’d get all hot under the collar, and his eyebrows would point downward like a pair of poison darts. A vein would pulse ever-so-slightly under his right temple, then it would bulge and BOOM! He’d be red-faced and spraying all sorts of stuff at his opponent: insults, slurs, spit, you name it.

But he knew how to handle his own and, in an odd way, the rest of his teammates saw all the arguing as a kind of compliment; a symbol that he was willing to place his own decency on the line to defend the troops. Made him a real general to the boys.

Physically, Williamson wasn’t much. Average at best. He was a consistent hitter and a decent defensive catcher with an above average arm. He was what people today might call “serviceable.” But he sure made up for it with a plump, juicy brain perched high atop his shoulders. That man could call a game with the best of them, both from the bench and from behind the plate. And I’m talkin’ about the heavyweights here, the real McGraw included.

He was followed in the lineup by the Canaries’ wily shortstop, Mr. William Wagner. Good old Willy secured his nickname early on in his Company League career. Since he played short and had the last name Wagner, he inevitably got the question, “Are you related to Honus Wagner?” “Oh no, I’m not,” he said politely on that first occasion and for many, many thereafter. It became a running joke in the league once the other players noticed it bothered him.

The truth was, Willy had a lot of pride in his talents. After all, the guy was like an acrobat out there on the field. He’d turn double plays that defied human ability, and made snap throws off balance like he was put on this Earth for that very purpose. If you ask me, the man was the closest thing to a poet I ever saw on a baseball diamond; simply amazing with the leather.

He was never quiet about reminding people of these talents. So, one day some jokester on another team said, “Hey kid, you related to Honus Wagner?” and started giggling, real obnoxious-like. Well, old Willy lost it right then and there. He called for time and announced to everyone in attendance he was “by no means related to that talentless busher who went by the name of Honus Wagner,” and that he “deeply resented the fact that anyone would put him in such low company.”

That’s when the umpire walked out to the mound, where the entire Canaries infield was congregated, and said, “Is everybody done?” Many of the players nodded or smacked their gloves in response. “Good…then let’s play some ball.” Then he looked in Willy’s direction and said with a wry smile, “That means you too, Honus.” And, of course, the name stuck.

Next in the order was “Sheriff” John Lawson. They called him Sheriff because his father was a police officer in town. Kind of convenient his last name also had the law in it. Most every man in the Lawson family had gone into fightin’ crime in some way or another, so they weren’t overjoyed by the route old Johnny had taken. But Johnny Lawson wasn’t the kind of guy who put much stock in the thoughts of others.

Coal breakers like these were used to seperate the coal from other mined material. Many still stand across the coal region.

He played left field for the Canaries, but he could have played any outfield position on any other team. It just so happened the Northern Coal team was loaded with talent, and Johnny possessed a touch less speed than Orange-Dust and a little less zip on his throws than Clean-Livin’.

But, boy, was that kid a luxury to have hitting in the seven-hole. It was like having another leadoff hitter to spark the 7-8-9 batting tandem. Sheriff was solely responsible for making his team the most productive bottom-of-the-lineup hitters I’d ever seen. He’d get on base any way he could and he’d steal bases relentlessly. If you put him on first, you better expect to see him on third in about two pitches. That’s all it took–and that with a little luck on your side. I can tell you this, and it’s the God’s honest truth: that boy would’ve swiped first base if the rule book had made it possible.

Johnny was a handsome man with straight, straw-blonde hair and a beard he kept tightly trimmed to his face. You couldn’t get his attention off a game of baseball if you fired a shotgun past his ear. But off the field was different. Boys on the team had to defend Sheriff more than once against an angry husband or a boyfriend who’d caught wind of Johnny buzzing around his lady. Nobody could ever get through to the boy in that respect.

After Sheriff came the slender but dangerous Perry Foghorn. He was the only member of the Canaries without a true nickname. Course, with a name like Perry Foghorn who the hell needs a nickname? His teammates took to calling him by his last name but would sometimes just shorten it to “Foggy,” which was an apt name because old Perry wasn’t the sharpest guy around.

Old Foggy had the damndest memory, or lack thereof, I’d ever seen. The only things the guy could keep in his head were baseball statistics and batting orders. And even those were a stretch on occasion. Course, nowadays you probably have some fancy-schmancy scientific name for Perry’s condition. Back then, we just called it ‘stupid.’

But if you put that man on a ball field, your attitude about him changed in an instant. He didn’t have the strongest throwing arm, but he made up for it with a fielding range at second base that nearly made the position of first base obsolete. And, boy, was he lethal with the stick. More of a marksman than a hitter, he could slap the ball to just about any location on the field at will. Wee Willie Keeler, “hittin’ ‘em where they ain’t,” was just a poor man’s Perry Foghorn in my humble opinion.

The Canaries pitcher was Ruben “Rube” Harriss. They called him Rube for obvious reasons, the most blatant of which was that his name was Ruben. Perhaps even more conspicuous was kid’s hayseed mentality. I mean, you had to be pretty rural to be called a Rube by anyone in those parts, especially in those days. But, by golly, Ruben Harriss earned every letter of that nickname.

By 1905, labor laws restricted children under 14 from working in the Anthracite coal mines, but “breakers boys” like these worked six days a week.

He was the youngest player on the team, but he possessed thick, broad shoulders and a pair of tree trunks for legs. He was barrel-chested and threw fireballs out of his left arm. The fastball would hum in there at God-knows-what-speed and leave a puff of smoke in its wake. But that’s not all he had. That boy perfected three, four other pitches. Most notable among them was what he called a “Bender.”

The Bender was what many people today might call a cutter, but Rube could throw it with scary success. It screamed in there at the same velocity of his fastball, but then jerked in on a righty’s hands at the last moment. This left the batter standing there with a pile of sawdust at his feet and a jagged section of lumber in his hands. Of course, Rube would have you believe he called it a Bender because anyone who faced it ended up in a barroom later that evening trying to drown out the misery.

Rube was usually dominant on the mound, but even when he was not, pure luck seemed to be watching over his shoulder. A good bounce here or there, an unlikely play, and suddenly Rube was nursing another win. That’s just how it worked for the youngster. A pile of cow shit could turn to gold if he stepped in it, so long as that pile was heaped in the middle of a ball field.

Company and church baseball clubs like this one from Oddfellows Cemetery in Centralia were commonplace in the Anthracite region.

Luck took a sinister turn on Ruben once he stepped off the field. Maybe he used every ounce of luck he had on baseball and had none left for himself. I don’t know. But you would never believe the things that happened to old Rube once he left the confines of Panhandle Park. It would almost be comical if it weren’t so damned tragic.

Boy, that sure was a team. Haven’t seen one like it since–and this region has been blessed with a great many talented ball players; a few Hall of Famers to boot.

The great spitballer, Stan Coveleski was from right on down in Shamokin. Another fine student of the tobacco ball, “Big Ed” Walsh, grew up just over in Plains Township. Even the best of them all, Christy Mathewson, with his patented fadeaway pitch, was a Factoryville boy. Old Matty played college ball right here at Bucknell. Might have sat in this very classroom for all we know.

But, I’ll tell you, there wasn’t a team around that was loaded with talent at every position like that Canaries team. Seemed like every player in the lineup was destined to do something great on a baseball diamond. I’m sorry to say it didn’t work out that way for the team from Northern Coal. They were cursed from the beginning, just like the town that gave them life…

TO BE CONTINUED

Come back next Thursday for Black Yarn Part 2/10 – “ORANGE-DUST”

Scott Perkel and Georgie Roland’s 2007 documentary on the town of Centralia and the life of its final resident, John Lokitis, is a masterpiece.

Watch “The Town That Was” in its entirety below (YouTube):

Pingback: In Case You Missed It: Black Yarn (A Fictional Series) | SOUTH PHILLY SPORTS CYNICS

Wow. Great piece of writing. Thanks for alerting me to the existence of The Town that Was. Gut wrenching stuff. Enjoyable film.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I couldn’t agree more about the story and the film at the end. John Lokitis? Damn, that guy makes Philly fans look dispassionate. Have you ever seen more loyalty?

LikeLike

Pingback: COMING SOON!!! Black Yarn: A Fictional Series in 10 Parts | SOUTH PHILLY SPORTS CYNICS

Pingback: Black Yarn: A Fictional Series (part 2/10) | SOUTH PHILLY SPORTS CYNICS

Pingback: A Random Tribute to Stan Coveleski | SOUTH PHILLY SPORTS CYNICS

Pingback: Black Yarn: A Fictional Series (part 3/10) | SOUTH PHILLY SPORTS CYNICS

Pingback: Black Yarn: A Fictional Series (part 4/10) | SOUTH PHILLY SPORTS CYNICS

Pingback: Black Yarn: A Fictional Series (Part 5/10) | SOUTH PHILLY SPORTS CYNICS

Pingback: Black Yarn: A Fictional Series (part 6/10) | SOUTH PHILLY SPORTS CYNICS

Pingback: Black Yarn: A Fictional Series (part 7/10) | SOUTH PHILLY SPORTS CYNICS

Pingback: Black Yarn: A Fictional Series (part 8/10) | SOUTH PHILLY SPORTS CYNICS